Advancing the Practice of CWPPs – Risk Modeling

Written by Corrina Marshall

The Forest Stewards Guild has worked with many communities in New Mexico and Colorado to produce Community Wildfire Protection Plans. For those who are unfamiliar with this type of planning document, it is a program that began in 2003, authorized and defined in Title I of the Healthy Forests Restoration Act (HFRA) passed by Congress. The plans are intended to shape wildfire mitigation and planning priorities for communities in the wildland-urban interface. A major goal of the legislation, when passed in 2003, was to convene diverse local stakeholders and interests to make decisions about their mutual concerns over public safety, communication, and natural resource management.

For the initial round of development, many communities were tackling their wildfire problem for the first time and began by defining their local boundaries and formally identifying locations of great risk. With many original plans being severely outdated, the Forest Stewards Guild has worked to update these documents to reflect changes in wildfire risk and community composition. Guild staff identified that clear plans outlining specific risks and locations for mitigation were lacking, and that the analyses completed on wildfire behavior did not capture all risk factors.

The planning process for previous CWPPs, in general, tended to not result in enough action on the ground, failed to engage local community members in the planning process, or analyze the complexity of wildfire risk. For this installment of ATL, we would like to share about our improvements to wildfire risk analysis. This is done by spatial analysis and wildfire behavior modeling based on vegetation data – that part is not new. What we have added to the CWPP process are products like evacuation modeling, post-fire erosion modeling, radiant heat & short- and long-range spotting potential, and treatment suitability analysis. A few examples below show the outputs from these models, a clear indication of where high priority treatments exist.

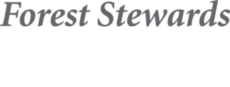

Figure 1. Evacuation Congestion in Evergreen Fire Protection District.

The model above shows us where evacuation congestion is likely to occur during a wildfire-influenced evacuation event. This can influence emergency response planners in knowing where to direct people, and land managers to better mitigate forest structure in areas where residents could possibly be stuck during a wildfire. Additional analyses show likely amount of time for certain neighborhoods to evacuate, and identify where wildland fuels against roadways will create non-survivable conditions, based upon flame length.

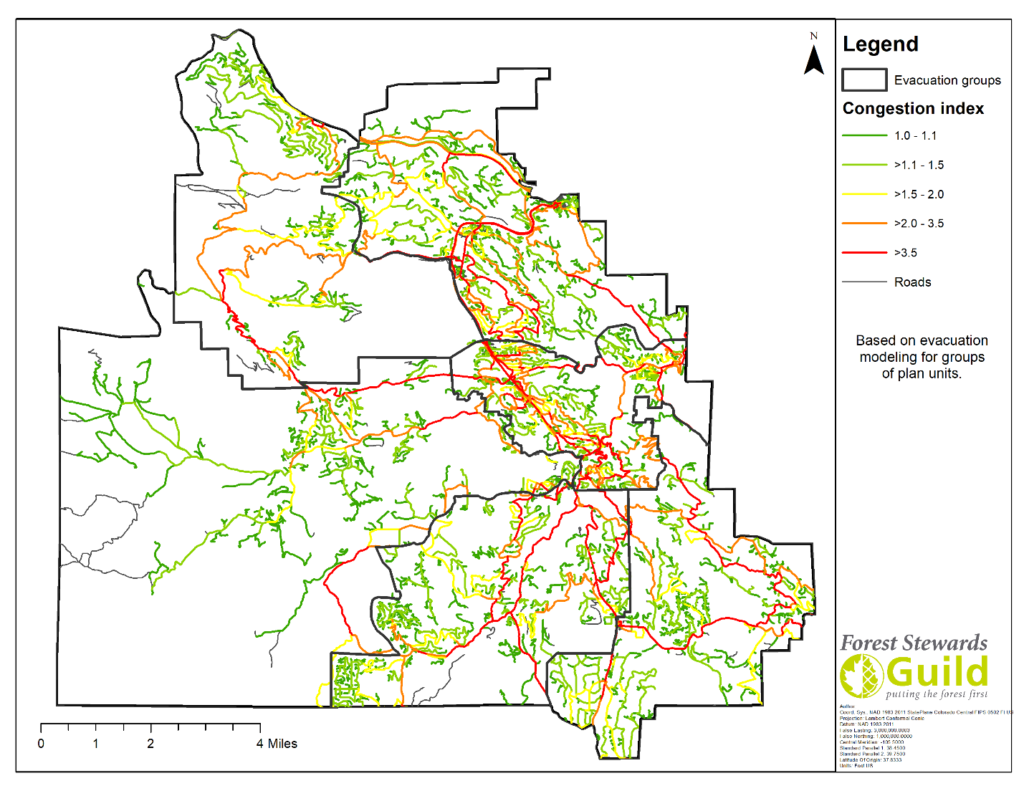

Figure 2. Post wildfire sediment delivery, caused by erosion, based on local weather conditions.

This information in Figure 2 is absolutely vital to this fire protection district to predict where catastrophic wildfire will have the most impact to watersheds and, in the case of this district, drinking water for a major municipality. This informs where wildland vegetation treatment should be prioritized to lessen the impacts of erosion, and if a wildfire is to occur, this can be a guide for prioritizing post-fire actions.

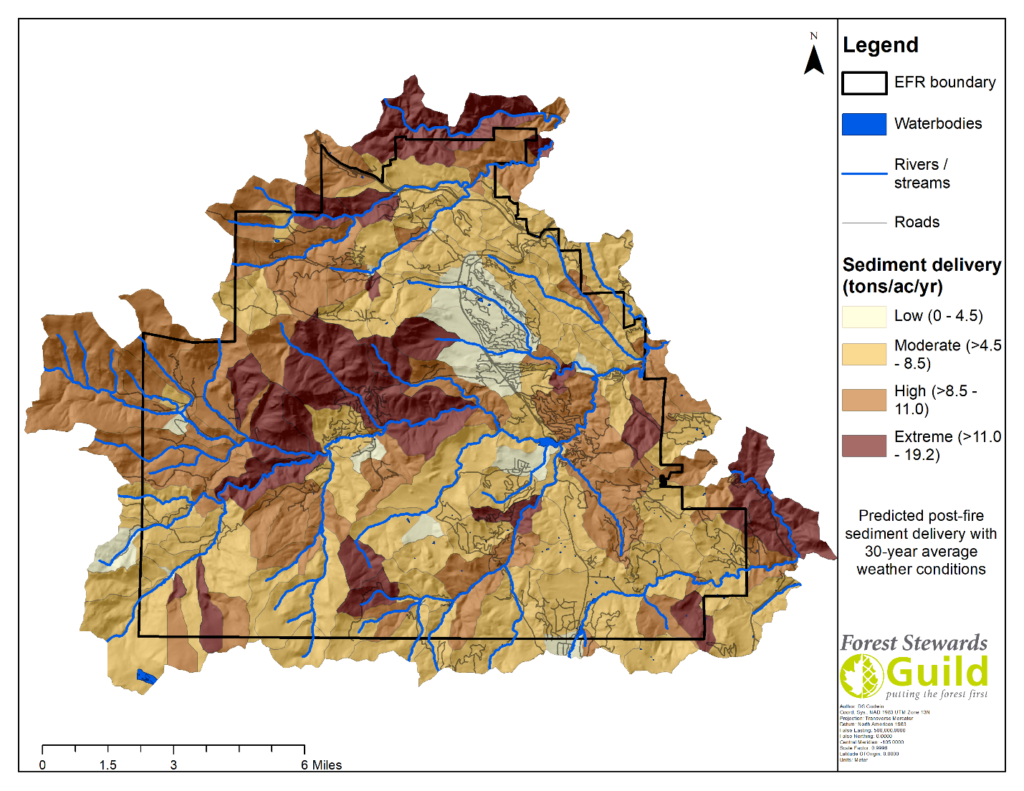

Figure 3. Radiant Heat and Short-and Long-Range Spotting in a neighborhood of Evergreen Fire Protection District.

The model in Figure 3 above is based on research done at the University of Alberta, defining radiant heat exposure to structures at 30 meters, short-range ember exposure at 100 meters, and long-range ember exposure at 500 meters from vegetation capable of producing those fire effects (Beverly et al., 2010). This helps districts and residents understand where homes are most likely to ignite from wildfire and where defensible space and home hardening practices should be highest priority.

Robust spatial analysis can predict where fire is likely to occur and how intense it is likely to be. This information, in coordination with local stakeholder input, really shows where priorities are on the landscape and where implementation is possible.

With these additions to the CWPP process, we hope to influence more effective wildfire mitigation and continue to develop new strategies to aid human and ecological communities in becoming fire adapted. In future articles, we will discuss strategies to improve community engagement and solidify actionable mitigation planning.