Northern Minnesota counties: A step ahead

Submitted by Mark Jacobs

Counties among first to receive approval for conservation plan

“Think global; act local.” The phrase has been used in numerous environmental and business planning contexts. It conveys an urgency for us to deliberate the health of the entire planet, but to take the necessary actions in our own back yards that can make positive impacts and contribute to global health.

Little brown bat

Bat surveys

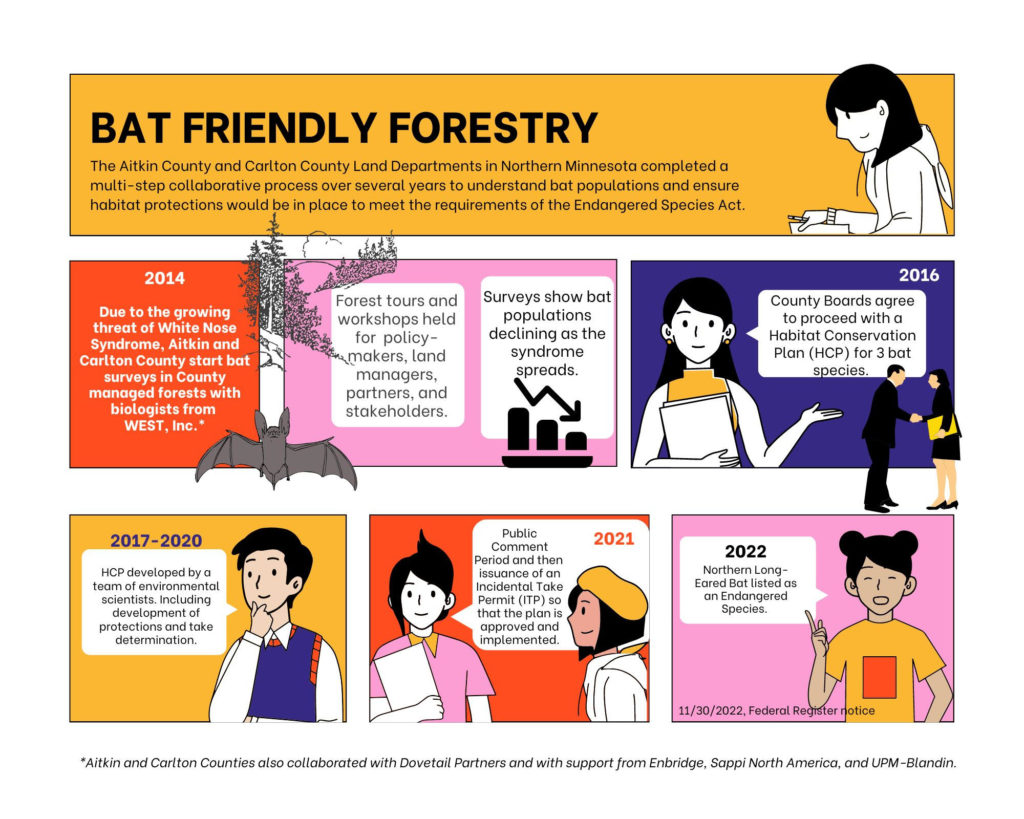

Two northern Minnesota counties have taken that axiom to heart. In 2014, Aitkin and Carlton counties began conducting ‘bat surveys’ in their respective county managed forested lands. They did so in coordination with Dovetail Partners, Inc., a natural resources think-tank based out of Minneapolis, and with support from Dovetail Partners, Enbridge, Sappi North America, and UPM Blandin Paper.

The impetus for these surveys was the growing attention to an increasing threat of a disease that is decimating forest-dwelling bats. The disease, “white-nose syndrome (WNS),” is caused by a fungus that prospers in cave environments. The fungus is believed to cause bats to arouse from their winter hibernation. In doing so, they deplete their body fat, which often leads to their death. The fungus was first documented in Minnesota during winter 2011-2012. The bats face extinction due to the range-wide impacts of WNS.

Endangered status and management planning

In conversations with bat biologists in early 2014, the counties were aware that, due to the rapid decline from WNS, an endangered status involving one or more local bat species was very likely. An ‘endangered species’ status can affect forest management: forestry operations and woodland activities can be restricted in the habitat area of an endangered species.

If a species is listed as endangered, “take” is prohibited. “Take” as defined under the Endangered Species Act, means to “harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect or to attempt to engage in any such conduct.” Incidental take is an unintentional, but not unexpected, taking. Forest management activities require an Incidental Take Permit (ITP) which is issued by US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS). The permit can be issued to private, non-federal entities, (like a county land department), undertaking otherwise lawful projects (like forest management), that might result in the ‘take’ of an endangered or threatened specie: in this case, the northern long-eared bat. Application for a permit is subject to certain requirements, including preparation of a habitat conservation plan by the person/agency applying for a take permit.

It sounds complicated; and it is. Land commissioners and foresters of Aitkin and Carlton counties embarked on those bat surveys early on, aware that the bat species might be facing the endangered status and that they would find it necessary to address the needs of the bat and the required permitting.

Planning a step ahead

Planning a step ahead

During those early years of their county land surveys, bats were found everywhere that biologists from Western EcoSystems Technology (WEST) surveyed – populations were high. After 2017, WEST found that bat populations had rapidly declined due to the presence of white nose syndrome in areas where the bats hibernated.

In 2016, Aitkin and Carlton counties made their commitment to consider the bat in their forestry activities by developing a memorandum of understanding which was approved by each respective county board. The memorandum directed the counties to proceed with a “Habitat Conservation Plan” for three at-risk bat species (northern long-eared, little brown, and tri-colored).

The habitat conservation plan was released for public comment about a year ago and has since been finalized. The finalized and approved habitat conservation plan is designed to avoid or reduce unintentional take of the bat species. The plan also provides measures to alleviate impacts of forest management on the bats when unintentional take occurs. The plan describes how an activity might affect the endangered species and how those impacts will be minimized or mitigated.

Guild members and others comment on the importance of having this in place

Having an approved habitat conservation plan is particularly important to Aitkin and Carlton counties – two forested counties whose economies are dependent on the management and sustainability of their natural resources, particularly their forests.

The counties’ habitat conservation plan’s approval by the federal government could not have been more timely. On November 29, 2022 the USFWS published a final rule to reclassify the northern long-eared bat from ‘threatened’ to ‘endangered’ under the Endangered Species Act.

According to Aitkin County Land Commissioner Dennis Thompson, “Developing the Habitat Conservation Plan was a long process but extremely rewarding to see the final product. I could not be happier with the cooperation and collaboration we have with Carlton County. The collapse in bat populations due to this disease is hard to comprehend but I know resource managers can play a role in creating and maintaining quality habitat for bats.”

The two counties were also issued an “Incidental Take Permit (ITP).” Approval of the plan and the ITP authorizes Aitkin and Carlton counties to continue to manage county forestlands in a sustainable manner with modifications related to activities near maternity roosts and known places of hibernation over a 25-year project duration. Carlton County Land Commissioner Greg Bernu notes, “We want to avoid the possibility of taking any bats.”

“The ITP allows us to continue our forestry operations with modifications. With these modifications in place we can harvest our forests, making the odds of taking a bat very small.”

Now-retired Aitkin County Land Commissioner Mark Jacobs, said that he and Carlton County Land Commissioner Greg Bernu felt “it was in the best interests of our local forests and local communities to develop our own HCP rather than sign on to a potential plan developed by others.”

According to Jacobs, “Based on bat surveys in our area prior to WNS, forest bats were doing very well in our managed forests. The intent of the HCP was not to drastically alter our previously approved forest plan, but to modify it to accommodate the bat species. For example, we adjusted the harvest activities over time and space to match critical periods in the bat’s life cycle and established specific practices to provide and protect roost trees.”

“The plan protects existing bats in the short term and in the long-term maintains/enhances habitat to facilitate their population recovery to pre-WNS levels.”

Kathryn Fernholz, President of Dovetail Partners, noted that the choice of the counties to take action has allowed them to stay a step ahead. “Forest managers face lots of challenges and changing conditions. We have the choice to take a “wait and see” attitude or to move forward and take action with the best available information and the knowledge of our professions. By conducting the bat surveys to gather additional information and then deciding to move forward with the HCP development, the counties have been able to reduce the risk of negative impacts to bats as well as to their operations and all of the environmental, social and economic benefits that sustainable forestry provide in Minnesota.”

As Commissioner Greg Bernu points out, “Taking care of our Minnesota forests means taking care of the other natural resources, like the bats that are dependent on them. One cannot predict how far-reaching the effects of our local stewardship go.”