Silviculture of Old-Growth Restoration in the Lake States

Written by Greg Edge, Wisconsin DNR Forest Ecologist/Silviculturist

Written by Greg Edge, Wisconsin DNR Forest Ecologist/Silviculturist

Photos by Wisconsin DNR

The recent Mature and Old-Growth Summit in Washington D.C. has focused attention on the interesting science of mature and old-growth silviculture. During the event’s regional breakout sessions, I had the opportunity to present the state of this science in the Lake States and reflect on how the silviculture of old-growth restoration has evolved over my career.

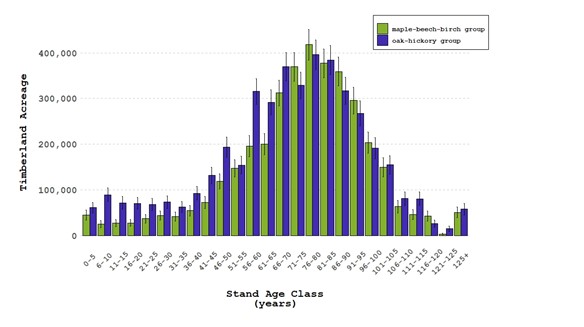

As forest practitioners we appreciate the importance of context, and this certainly applies to managing old-growth in the Lake States. Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan all fall at the intersection of the eastern temperate forests, northern boreal forests and tallgrass prairies, resulting in significant transitions in climate, soils, glacial history, and vegetation. This makes defining and managing old-growth or old forests vary depending on the wide variety of forest types found in this region. The “Cutover” period of the past two centuries has resulted in a legacy of predominantly second-growth forests. Wisconsin’s overall age-class distribution for the maple/beech/birch and oak/hickory forest type groups is very even-aged, with little young forest and even less old forest.

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) staff estimates that less than 1% of all forestland in the three states contains old-growth by applying the recently published Forest Service working definitions to statewide Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) data. Therefore, the greatest opportunities to manage old-growth and old forest characteristics lie in these second-growth forests.

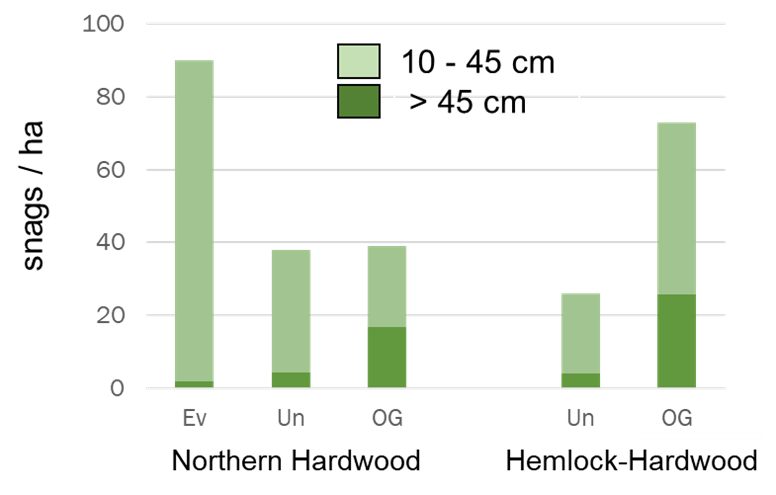

Much like the rest of North America, the 1980s and 1990s brought greater attention to old-growth forests and management in the Lake States. Craig Lorimer, Ph.D., and David Mladenoff, Ph.D., at the University of Wisconsin – Madison and Wisconsin DNR research staff began an effort simply known as “the old-growth project.” The first goal of this research was to compare the composition, structure, and function of remnant tracts of old-growth northern hardwood forests, such as those on Michigan’s Sylvania Wilderness, with that of second-growth northern hardwoods managed under even and uneven-aged systems. Lorimer’s lab found significant differences in structural components like snags, downed wood, large trees, canopy gaps and windthrow mounds. Differences were also found in functional attributes, like fungi and nutrient dynamics.

Around this same period, the arrival of third-party forest certification programs and the development of ecological forestry concepts hastened the establishment of state silvicultural guidance to address ecological aspects of old forests. This included state definitions for legacy trees, old-growth and High Conservation Value Forests (HCVFs), and the development of tree retention standards in all three states. In recent years, ecological silviculture or forest management based on natural disturbance models has been incorporated into guidance, such as the Minnesota DNR Native Plant Community Silviculture Strategies and the Wisconsin Silviculture Guide.

Coming out of “Phase 1” of the old growth project were a group of studies that looked more closely at the differences between old-growth and managed stands. The largest of these was the Managed Old-Growth Silvicultural Study (MOSS), a 50-year operational study comparing silvicultural methods for accelerating the development of old-growth characteristics, along with forest products production. MOSS was established at three locations in 70-90 year-old second-growth northern hardwood stands in northern Wisconsin. The 1600-acre experiment built off Lorimer’s work, testing several treatments to accelerate old-growth structure, including small gaps (35’), large gaps (60’ and 80’), irregular multi-cohort openings (emulating moderate windthrow), thinning, snag creation, coarse woody debris creation and controls. Early results indicate that creating coarse woody debris and snags and leaving large reserve trees did not immediately reduce the economic viability of the treatments. In addition, girdling trees to create snags was effective, and the longevity of these structures varied according to species and tree size.

Coming out of “Phase 1” of the old growth project were a group of studies that looked more closely at the differences between old-growth and managed stands. The largest of these was the Managed Old-Growth Silvicultural Study (MOSS), a 50-year operational study comparing silvicultural methods for accelerating the development of old-growth characteristics, along with forest products production. MOSS was established at three locations in 70-90 year-old second-growth northern hardwood stands in northern Wisconsin. The 1600-acre experiment built off Lorimer’s work, testing several treatments to accelerate old-growth structure, including small gaps (35’), large gaps (60’ and 80’), irregular multi-cohort openings (emulating moderate windthrow), thinning, snag creation, coarse woody debris creation and controls. Early results indicate that creating coarse woody debris and snags and leaving large reserve trees did not immediately reduce the economic viability of the treatments. In addition, girdling trees to create snags was effective, and the longevity of these structures varied according to species and tree size.

Overall, commercial harvesting reduced the number of snags within stands, partly due to safety requirements. MOSS recently completed year-15 measurements and is analyzing these data.

However, not all old-growth in the Lake States looks the same! This is especially true in our frequent, low-severity fire communities. A new research study led by Wisconsin DNR research scientist Dr. Jed Meunier looks at silviculture methods to emulate the diverse spatial and regeneration patterns of natural origin red pine. The Northern Pine Management Initiative uses the individuals, clumps and openings (ICO) method to establish variable density thinning targets based on historic stand structures. The study includes ICO thinning, standard basal area thinning, and controls at three northern Wisconsin sites. Prescribed burns will be applied in half the treatment blocks to emulate the historic disturbance patterns.

However, not all old-growth in the Lake States looks the same! This is especially true in our frequent, low-severity fire communities. A new research study led by Wisconsin DNR research scientist Dr. Jed Meunier looks at silviculture methods to emulate the diverse spatial and regeneration patterns of natural origin red pine. The Northern Pine Management Initiative uses the individuals, clumps and openings (ICO) method to establish variable density thinning targets based on historic stand structures. The study includes ICO thinning, standard basal area thinning, and controls at three northern Wisconsin sites. Prescribed burns will be applied in half the treatment blocks to emulate the historic disturbance patterns.

The maturing second-growth forests of the Lake States and the realities of our changing climate will require us to continue developing our understanding of mature and old-growth forests and expand the silvicultural toolbox available to forest practitioners charged with managing these forests.