Rethinking Red Pine: Forest Diversity and Resilience in the Great Lakes Region

Written by Christian Nelson, Lake States Coordinator

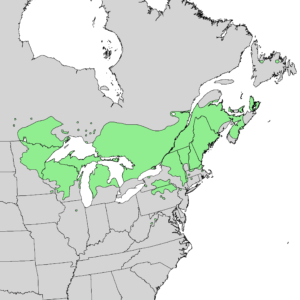

Red pine (Pinus resinosa) forests have long been an iconic feature of the Great Lakes region. Often towering 100 feet or more above the ground and with three-foot diameter trunks, “Norway Pine”, as Minnesotans sometimes call their state tree, is tall, straight, and relatively knot-free. If properly thinned, red pine have little taper and grow quickly, making them commercially valuable. They are affected by few plant diseases or insect pests and grow quickly.

Planted en masse during the 1930s Great Depression era by Civilian Conservation Corps crews, and again in the 1960s by county and state foresters, red pine was the tree of choice for generating income on tax-forfeited farmland. Nearly 100 years after those first trees were planted in tidy, evenly spaced rows, and in the face of rapid climate change and shifting values, land managers across the region are reimagining what red pine forests can — and should — look like in the future.

Red pine forest in the mist at night, credit: Eli Sagor

A Legacy Planted and a New Direction?

Today, more than 75% of red pine forests in the U.S. exist as plantations, many of which are aging and increasingly vulnerable to pests, drought, high winds, and ice storms. Stands that have been well managed may have trees growing too large for sawmills optimized for moderate-sized pines. Neglected stands are crowded stands that may have trees with strong taper and slow growth rates and be especially prone to windthrow, ice damage, drought stress, and insects or other diseases. Pulp markets for small-diameter trees are weak or absent in many areas.

Historically, red pine was found in mixed stands of up to a dozen other species. Periodic fires exposed mineral soil and killed overstory trees and shrubs, boosting sunshine reaching the forest floor and providing fire-adapted seedlings the conditions they need to germinate and thrive. Lightning started some of these fires but many more were intentionally lit by local Indigenous populations using fire as a tool to open up areas for hunting, to create fresh browse for game animals, to clear areas for small scale agriculture or habitation, and even to decrease swarms of biting insects along travel routes in an era before Deep Woods Off and mesh bug suits. Some areas were burned frequently resulting in a more open, park-like landscape with only large, fire-tolerant species like jack-, red-, and white pine, or oaks. Some fires were large crown fires that killed the largest trees in the stand

Red Pine range map. Source: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pinus_resinosa#

and created natural openings on the forest floor. Other areas, perhaps wetter, sheltered from the wind on the leeward side of a beaver pond, or burned overnight when the temperature cooled and the winds diminished, left the overstory untouched and an understory that was as different as the flames that carried through.

In the late 1800’s, European settlers trying to prevent large wildfires from burning across thousands and thousands of acres of post-logging slash, adopted a hard stance against the use of fire. This included the traditional or cultural burning practices of tribes, who were fined brutally if caught. As technology and infrastructure improved, settlers got better at limiting the area of land burned every year. This had – and continues to have – important ramifications for the millions of acres of forests that evolved with, and depend on, fire to perpetuate themselves on the landscape. Red pine forestry in the region, with an emphasis on growth, yield, row-crop harvesting efficiency, and economics, has grown stands with little structural or species diversity, limited ecological value, and increasing vulnerability in a period of accelerating climatic change and the threats and stressors that come with it.

Managing for Resilience, Not Just Yield

The shift underway across the Great Lakes region marks a transition from the forestry of the past two centuries — focused on maximizing red pine growth — to an ecological approach that values biodiversity and therefore resilience. Ecological forestry in red pine forests may include:

- Variable retention harvesting (VRH): Where thinning occurs in groups or patches and may leave the surrounding matrix untouched. and where existing groups of trees -old, large, or non-pine-collectively referred to as “legacy trees,”, are left standing to preserve habitat complexity and biodiversity. In a given stand, trees of different species or ages may occupy different canopy layers. Throughout the stand, tree species and size, density, and the locations of openings should be heterogeneous. This is a markedly different forest than the evenly spaced, same-age, same-height, monoculture red pine plantations of the last several decades and more closely resembles historic red pine stands. Dense stands may need crown thinning throughout the stand ahead of VRH treatment.

- Site selection: Evaluating soil water and nutrient properties, regional native plant communities, or habitat systems, to assess the suitability of the site for red pine and other species now and into the future. High quality sites may provide the best opportunities for ecological management. Areas with red pine growing on poorly suited sites, especially if already showing signs of distress, should be considered for transition to a more suitable species mix.

- Species selection: Using current habitat type information along with climate change predictions to favor tree species predicted to tolerate the current and predicted future climatic conditions. This may mean planting trees with genetic stock sourced from warmer areas, or planting species not currently native to the local area but present in the larger region.

- Understory enhancement: Encouraging shrubs, non-pine trees, and coarse woody debris (downed logs) using silvicultural techniques like gap creation, scarification or mechanical brushing, and using prescribed fire with variable intensity, frequency, and layout.

- Habitat enhancement elements: Including the ecological forestry elements from above and other important features such as: large standing dead trees (snags), some canopy gaps in a “pre-forest” condition, and invasive species control.

- Extended rotation ages: Red pine responds well to thinning, specifically a reduction in crown competition, even as tree age surpasses 100 or more years. Crown thinning every 10-15 years helps keep live crown rations in the 30-50% range, optimizing growth rates and the ability for the tree to utilize new space. Done properly, economic returns on stands with extended rotation ages are on par with traditional short rotations. Extended rotation forestry can help achieve ecological goals while remaining economically viable.

Restoring Diversity, Restoring Resilience

Red Pine cone photo credit: Eli Sagor

Ecological forestry, specifically increasing biodiversity, doesn’t mean abandoning red pine. The goal is to restore the complexity and broad value of historic red pine dominated forests by mimicking the natural and historic disturbances that created them. Complexity is largely absent when managing red pine like a row crop and in an age where logistics make regular burning difficult.

In plantation settings, tools like prescribed fire, mechanical thinning, gap creation, girdling, and planting suitable but underrepresented species can be used to mimic the forces of wind, and especially fire, that once shaped red pine ecosystems.

Today’s Forestry, Tomorrow’s Legacy

The Great Lakes region’s forests are not locked in time but they are locked in place. They are living systems in a dynamic environment that is changing quickly all around them. Building resilience into red pine stands today means healthier forests tomorrow.